= More info =

Public Spaces, Following the Development of a Historic City

Tatia Gvineria

Probably, everyone who at least once has seen archival photos of old Tbilisi has dreamed of walking in that distant, unknown city, where in parallel to the familiar places, we see a mysterious town with its heart open to the river, streets, squares, markets, and public gardens. Here, you feel the turbulent life and find yourself at a meeting point between Eastern and Western cultures. While looking at it, you realize that this is your city, which is remarkably close and, at the same time, quite distant, with many references that connect and simultaneously separate you from it.

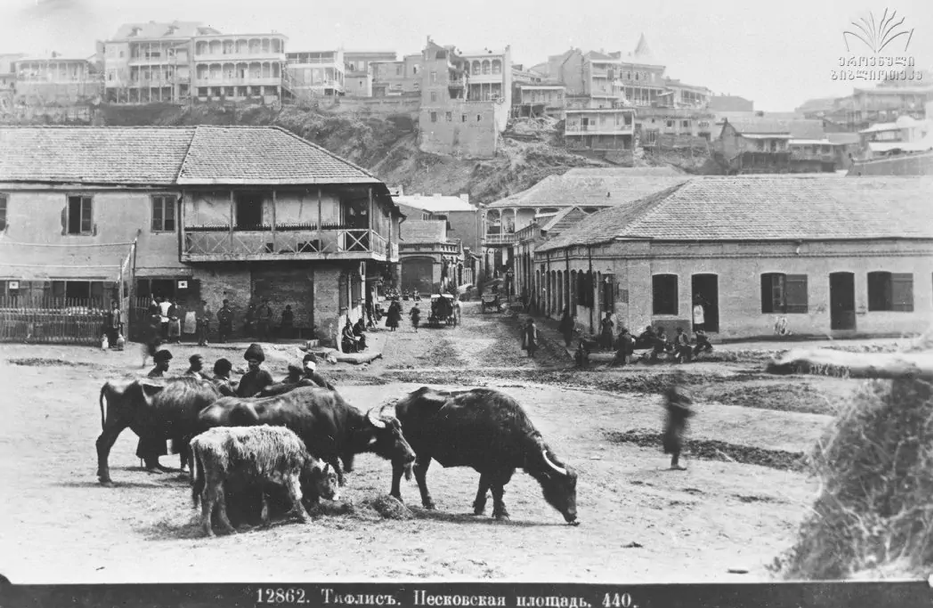

Rike, Tbilisi, XIXc.

This city has withstood for centuries, lost a lot, and still survived with its streets, houses, courtyards, squares, memories, the river running away from it, and people who were and still are its principal value.

Kala, Tbilisi, 1910s

The city is a living organism that constantly responds to the changes of times (good or bad). Each change gets imprinted in its body like a wound. However, as soon as one touches its depth and tries to learn more about it, the city's heartbeat starts talking about its pain or invisible desires.

According to Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani: "A city is a place of cohabitation full of a multitude of people, as one person is not sufficient. Humans need to help one another and multiply the benefit."[1] Correspondingly, the city is a shared living space for people and their unity. It is a commune that creates a society and develops its rules and customs, which are determined based on life, needs, existence, and political and social demands. The coexistence of people, in the process of shaping them into society, establishes the necessity of their communication that is expressed in public spaces - locations "open and accessible to all people, regardless of their gender, race, ethnic origin, age, social and economic level" (UNESCO, 2017).

Many things can be defined as such spaces, including the squares, gardens, streets, riverbanks (an extremely sensitive issue) that have already been lost for Tbilisi, and the remaining Tbilisi courtyards, which still shape the city itself.

These are the spaces designed for communication and carrying the principles of equality and democracy, simultaneously conveying the spirit of the city, its identity, and urban context very precisely.

Athens, Agora

One of the earliest classical forms of public spaces, the Greek Agora, represented the center of the Greek polis's political, economic, and social life. Agora literally means a "place of assembly" or "gathering," which practically gave birth to the idea of Western democracy. It was an arena for political discussion and participation, and at the same time, it created a meaningful urban hub for ancient cities. The Roman Forum is a public space similar to the Greek Agora. However, unlike the Agoras, they have a distinctly geometric, mostly rectangular shape enveloped by porticoes. The Forum served religious and civil functions, the main idea of which was a public gathering.

One will be surprised, but a similar planning arrangement of a square can also be found in the ancient complex of Uplistsikhe, where the urban architectural center of the former city shows its functional purpose of offering the population a place to get together.

In the Middle Ages, religious institutions in historic cities turned into public spaces; however, during this period, the trading locations that were often organized in or next to the temples became significant. In these cases, the space/object was also the epicenter of the urban fabric.

The structure of the medieval cities can still be read in the design of Georgian settlements, including Tbilisi's layout and formation, where the squares and the trading centers play the role of a nucleus that spreads out the functional urban network.

Place Vendôme, Paris

In European settlements, in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the focus shifted to the urban planning of the cities. Consequently, their central axis, i.e., the public space, was carefully planned and, in many cases, included in the general plan of an entire structure. This is where public spaces and art synthesis, and cooperation came together. However, the following era of European Modernism was less concerned with the historical role of public spaces. It used a new vision of a "form that matched the function" to embrace the idea of extended open locations. Thanks to its scale, the public space lost its function of intimate sociability and transformed into a fascinating place that matched new needs. Public spaces play a significant role in European cities, even during political and social unrest, when they become the epicenters of public voice. The 1960s produced the notion of the "right to the city," which implies the population's control over an open space.

The next stage of the development of historical settlements in Georgia, which became typical for almost all large Soviet cities, brought new urban tasks. While designing pompous, ideologically favorable places, the focus shifted to creating new public spaces and transforming the old ones. This caused not only the destruction of individual buildings in Tbilisi but also the complete disappearance of historic districts and the most important public spaces of the city, including the most painful framing of the banks of the Mtkvari River and the erasing of the Rike district.

At the same time, the city created new, splendid public spaces, the shape and ideology of which were designed to gather large masses of people. Of course, in addition to the emergence of unified spaces, it was essential to introduce monumental images. A clear example of the trend is the former Republic and, currently, Rose Revolution Square, which never managed to acquire the function of a square, and its public designation remains a conditional notion even today.

Republic Square, Tbilisi, 1982

Republic Square, Tbilisi, 1993

In the classical sense, the correct design of public spaces in modern cities should reflect the requirements of the city's population and play an essential role in their social and cultural life because people create spaces, and their needs should be adequately reflected in their appearances and quality.

We should separately analyze the installment of artworks in public spaces and their function, which can be perceived as an ontological[2] task of the social and cultural reflection of society.

Art placed in the public space is directed at the general public, should secure accessibility, and is primarily responsible for the social quality of the city's urban locations. It should specifically protect and outline the historical memory related to a specific space, promote the improvement of spatial, architectural, or urban situations, and, most importantly, develop an adequate shape for the era.

Nevertheless, the ideological relationship between the society and the represented art can be completely different, although it must respond at least to the basic requirements of the shared space; otherwise, if it remains utterly devoid of form, it will not manage to get integrated into the standard body of the space. We have many examples of this situation in Tbilisi.

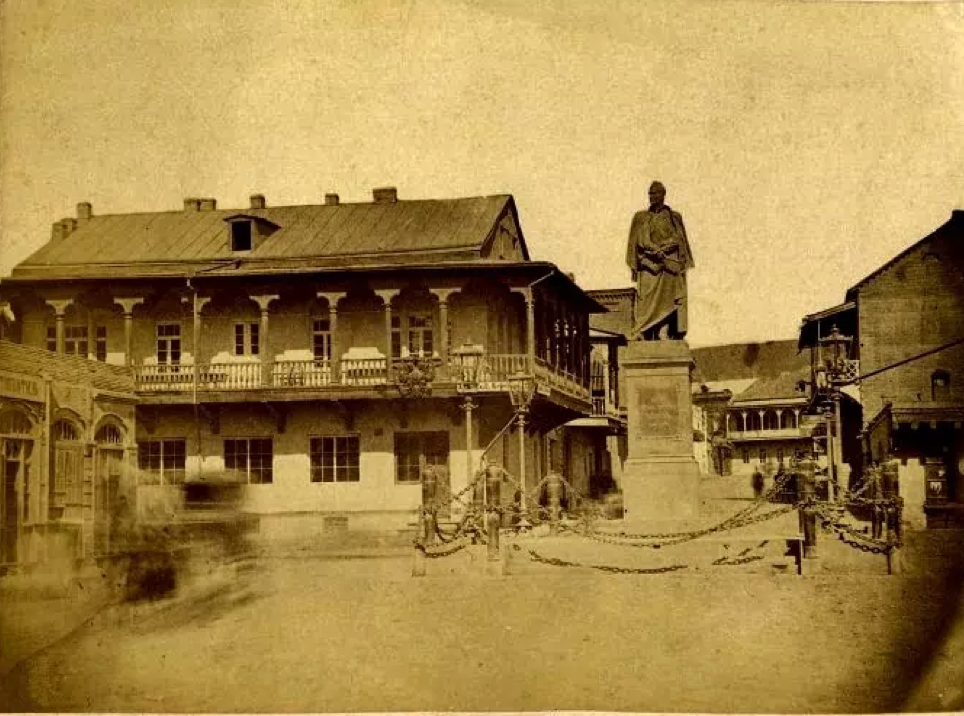

If we look at the city's historical development, we will see that the placement of monumental art in public spaces began at the end of the 19th century. The first monument was erected in 1867 to celebrate the 22nd anniversary of the arrival of Crown Prince Mikhail Vorontsov in Tbilisi. It was the first circular statue in the capital that resembled its counterparts from the European cities. Its installation was a great honor for the town and filled it with pride.[3] The history of monument erecting in Tbilisi began in the 19th century. The Soviet government found an incredible way to use the fact for its ideological propaganda. It later turned the trend into a boom of monuments saturated with a pseudo-national flavor. The entire process became part of a kitschy sham hysteria during the last decade. The issue of the circular statues is a subject of separate discussion, and we will wait to dwell on it. However, the social and cultural phenomenon of the public spaces of the historic city, which existed before the circular statues or emerged at the same time, is quite interesting.

A monument to Vorontsov, Tbilisi, 1882

Were not the "Salakbo" (A Place of Mere Verbiage) or the square of "Ambavists"[4] (Story Tellers) in Tbilisi, classic examples of public spaces of living intangible heritage reflected the organicity and importance of locations that emerged from the needs of the society. Or even the notion of the Mtkvari embankment as a single public space that would bring together the city's population?

Salakbo, Tbilisi, 1910s

River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, 1905

Both listed examples no longer exist in the city; however, due to the communal activity and "the right to the city," the population managed to save Gudiashvili Square, one of the most essential urban hubs of the Kala district.

However, Niko Pirosmanashvili, who developed himself in public space and was perceived from this niche, is the most organic phenomenon of the city and its social and cultural spaces. Most of Pirosmani's works were advertisements placed on the facades of inns to offer a live exhibition to specific streets, districts, or cities.

"Traditional exhibition is conceived as a collection of art objects placed next to each other in the exhibition hall and intended to be viewed one after the other. In this case, the exhibition space functions as a neutral, public urban space."[5] – notes Michel Foucault in his letter. So, how did the traditional exhibition differ from Pirosmani's "public display," those streets and inns that showed his paintings? That is why the phenomenon of Pirosmani, organic to the point of genius, accurately represents a social and cultural urban myth that emerged from the city's heart.

Public spaces are a connecting link of multi-functional social relations that works on urban, social, and economic issues in a multifaceted way. However, their most vital component is art, a reflection of the city as a living organism transformed into a specific work. How a piece of art brought to life in different media and projects should be is undoubtedly something the authors themselves need to come up with.

Tatia Gvineria

Tatia Gvineria (b. 1981) is a Tbilisi-based art historian and cultural heritage expert. She graduated from the Tbilisi State Academy of the Fine Arts, Faculty of Art History, in 2003 and is currently pursuing her PhD in the same institution. She has participated in a number of important studies including "Cultural Heritage Management Plan", EBRD; "Gori Fortress. Visitor Infrastructure Project Concept", USAID; Kutaisi General Plan, Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure of Georgia; "Support of the Culture Committee of the Parliament of Georgia for the protection and development of historical fortification areas", UNDP; "Restoration concept N. Firosmani Street, I. Kargareteli Street, D. Aghmashenebeli and Saarbrucken avenues,’Dry Bridge’ and Orbeliani Square", Tbilisi City Hall; "Cultural Heritage Monuments in Batumi", Adjara Cultural Heritage Protection Agency. She has curated numerous exhibitions including “Pirosman in Tsinandal", "Once in Holland - Piet Mondrian", "Salvador Dali in Tsinandal”, Silkroad Group. A number of articles have been published under her authorship, including "The Unknown History of Tbilisi House" Coup de Fouet, 2021, "The World Sculpted from Black Background", NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Georgia.

[1] Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, The Georgian Dictionary.

[2] Definition: To characterize events in terms of the laws of objective reality.

[3]Galaktion Tabidze’s notebook reads: "Vorontsov stands there with one of his legs put forward and holds his coat with both hands. He holds a rolled-up paper: this means business, a plan. There is some inscription on the monument, which is higher than a two-story house. The statue is surrounded by a chain attached to four low cannon-like columns: could these have been gun barrelsof the cannons? The pedestal has three stone steps on the eastern and western sides and the southern and northern shoulders. Akaki Tsereteli wrote a poem about the monument. In the story, Vorontsov is presented as a hero (“That man was called Vorontsov, and he was a hero of heroes; I think of his times as an old man, my son, and that’s the reason for my tears”). After a long time, after the revolution, I saw this monument in the courtyard of the historical museum. His steel legs were sawn into two."

[4]"Ethnographic Tbilisi": "There were no newspapers in the old days. Nor are there any now, but Georgians never lacked news: they looked for and found them. Oral ones substituted the printed newspapers. Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, transmitted news to every side. The news was distributed in Tbilisi from the Square of the Story Tellers. This was a place of gathering where people would learn from each other about the four corners of the country,the state of the people, and the locations of the happenings. They even discussed the political secrets from the royal halls, whether real or modified, but brought to light, investigated, approved, or disapproved of.“

[5] Michel Foucault, Installation Politics.